Reparative genealogy seeks to uncover and reconnect stories, people, and histories that were disrupted or erased. Lottie Lieb Dula and Briayna Cuffie, founders of Reparations4Slavery, define reparative genealogy as “the act of researching our heritage, acknowledging our connections to slavery, and daylighting the history of those our ancestors enslaved.”

Imagine discovering a photograph of a long-lost ancestor, reading their name for the first time, or learning about their resilience in the face of unimaginable hardship. These are some of the potential benefits of reparative genealogy. African Americans often face genealogical roadblocks such as incomplete records, name changes, and erased identities. The gaps in these narratives are not just personal but systemic, reflecting a deliberate history of exclusion and dehumanization. Overcoming those gaps can provide benefits. Lakisha David has described the potential of genetic genealogy to build community and improve well-being in African American individuals and communities. Reparative genealogy isn’t just about the past; it’s about the present—giving voice to those who came before and creating a foundation of knowledge for future generations.

Reparative genealogy is about more than restoring a family tree; it’s about the descendants of enslavers acknowledging harm and making amends through research, documentation, and storytelling. By uncovering forgotten or hidden histories, descendants of both the enslaved and enslavers can address the gaps left by historical injustices.

In 2021, Danette Ross, the founder of a non-profit and trained mediator, decided to learn more about her family history. We worked together using documentary evidence and DNA to explore her origins. She was curious about which African countries her family descended from. She also wanted to learn about her family’s experience during Reconstruction. Danette knew that most of her ancestors had likely been enslaved, and some could be enslavers.

Danette’s Ancestral Regions confirmed her prediction, showing both African and European ancestry with possibly a small proportion from Southeast Asia.

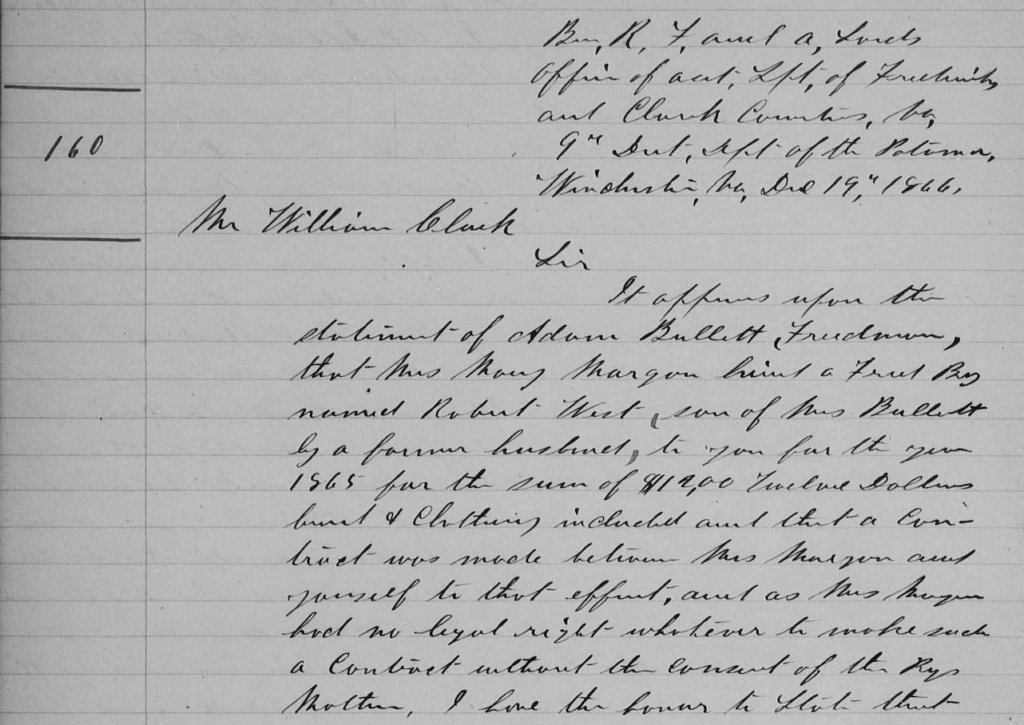

In answer her second question, an 1866 letter written by an official in the Freedmen’s Bureau office in Winchester, Virginia provided a glimpse of the Reconstruction experience of one ancestor. Danette’s 3x great-grandfather, Adam Bullett, traveled to Winchester and asked the official to write a letter on behalf of his wife and step-sons. They were owed wages because they had been illegally hired out by Mrs. Mary Morgan to two different men. This letter highlights the challenges that newly freed people faced in gaining control over their work and income.

Here are some practical steps to get started with reparative genealogy, starting with personally held information and expanding to public resources:

- Family oral histories

- Old photographs

- Historical family documents that may acknowledge enslaved people

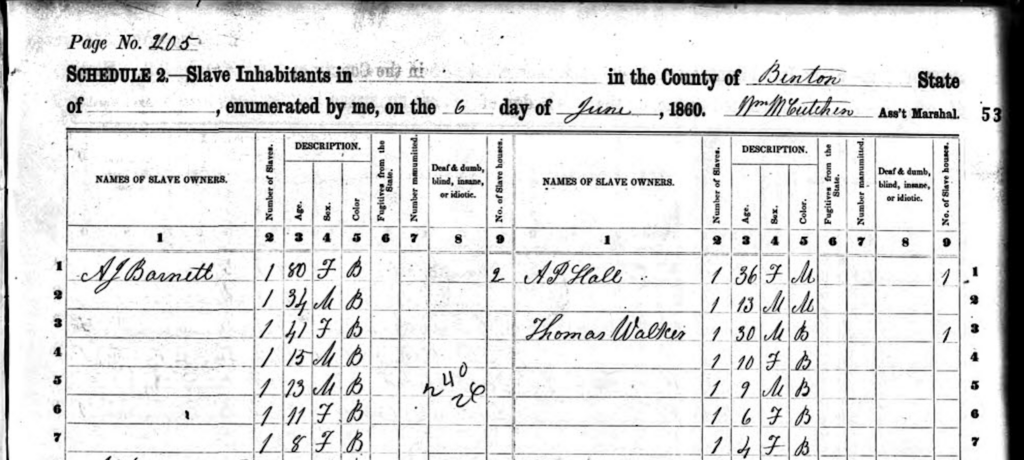

- Census data, particularly the census records from 1790-1840 and slave schedules from 1850 and 1860 (example below)

- Freedmen’s Bureau records

- Deeds, Wills, and Bills of Sale

- DNA testing

Collaboration between the descendants of the enslaved and enslavers supports builds a better understanding of the past and can inspire actions of repair. Linked Descendants is a working group of Coming to the Table, an organization dedicated to “working together to create a just and truthful society that acknowledges and seeks to heal from the racial wounds of the past.” The process of building these bridges can be as meaningful as the discoveries themselves. Some of these stories are told in Bittersweet, the blog by authors who are linked through slavery.

Another notable effort in reparative genealogy is the U.S. Black Heritage Project at WikiTree. WikiTree allows creation of profiles of those who were enslaved, including people whose names are not currently known. You can read more about it in this blog post I contributed to the Family Locket blog. Volunteers are currently creating profiles for every African American enumerated in 1880, the first census which noted relationships within households. Ten Million Names is an effort of the New England Historical and Genealogical Society to recover, restore, and remember those whose lives were hidden in the system of chattel slavery. You will find free education, access to records, and more on the website. There are many more resources in African American genealogy, and a good place to start is at the FamilySearch Wiki.

Reparative genealogy offers a way to acknowledge the past while shaping the future. It reminds us that the work of repair is ongoing and every piece of history we uncover is a step towards a better future. If you are a descendant of an enslaver, consider how you can contribute to reparative genealogy.

Use of AI in this blog: I asked ChatGPT 4.0, as an expert genealogist and educator, to provide three outlines for a blog on the topic of reparative genealogy. As part of my prompt, I told Chat GPT that I would provide a case study. After reviewing the three outlines, I chose one and asked ChatGPT to write a draft. I reviewed the draft, edited it, and added definitions and links. I added the case study which I asked ChatGPT to review for excess wordiness or errors in tenses. There were no changes made to the case study. I then reviewed the draft, added the images and published it.