I look forward to learning about the new tools and updates that come from DNA testing companies. Recently Ancestry.com updated their genetic communities. Genetic communities demonstrate the link between genetic genealogy and traditional documentary genealogy research. Ancestry uses the family trees of customers and the power of their massive autosomal DNA database (over 21 million testers) to place groups of ancestors in a place and time. The time frame (starting about 300 years ago) matches the time period when documentary evidence might be found. DNA communities provide hints for further research.

Autosomal DNA inheritance is random and siblings (unless they are identical twins) will have different results. My brother and I each received half of our atDNA from our dad and half from our mom, but we didn’t get the same half.

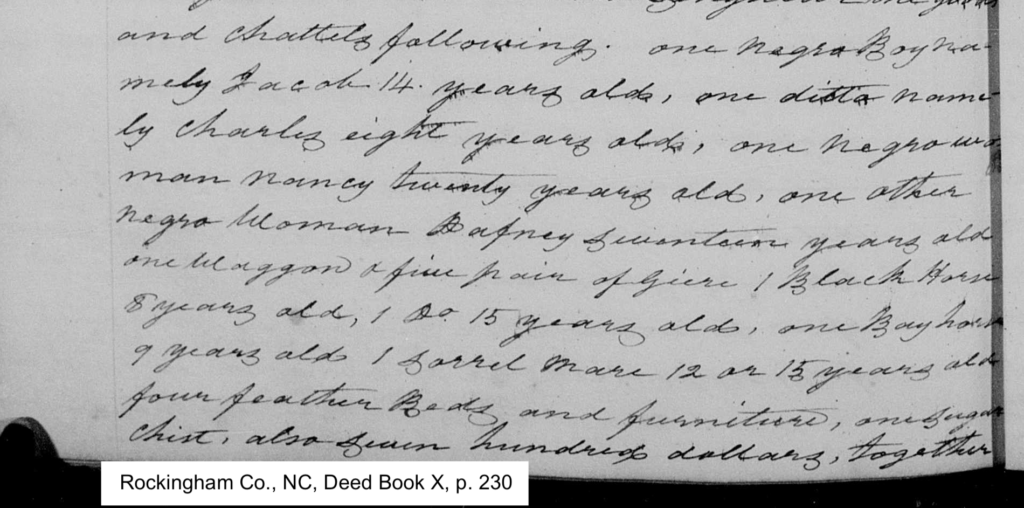

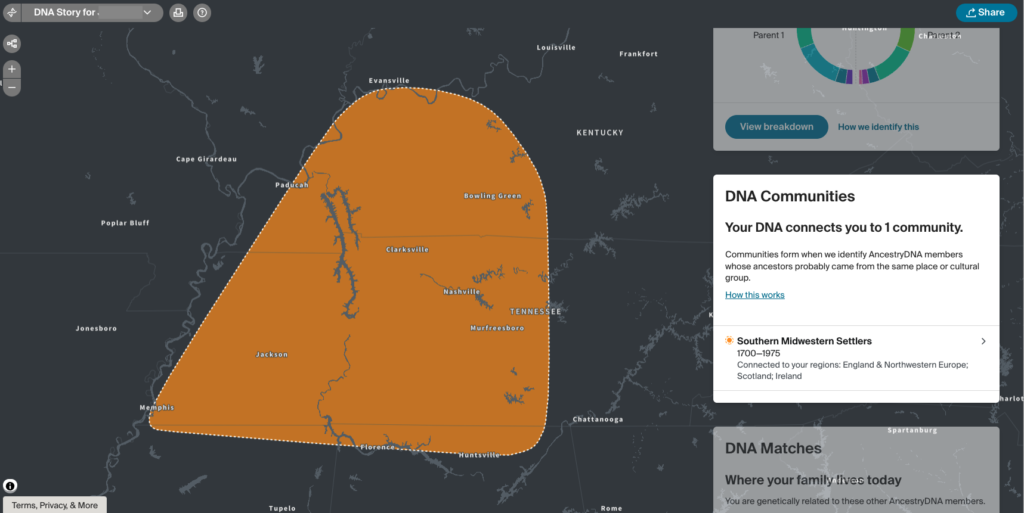

My results aren’t very impressive:

I have one community. Clicking through the information tells me which DNA matches and which ancestors fit in this group.

Here are the results for my brother:

The DNA Community for my brother is different than the one I have. One of the same 4x-great grandfathers on my maternal side, Holloway Key (1777-1855), is in both groups. This makes sense since the geographic area of Tennessee where he settled appears in both. For my paternal side, there are hints I can pursue in the Lower Midwest & Virginia Settlers group for the House family that I am curious about.

I tested my mother before she passed away, and her brother (my maternal uncle) also agreed to test. That puts me one generation closer to my maternal ancestors.

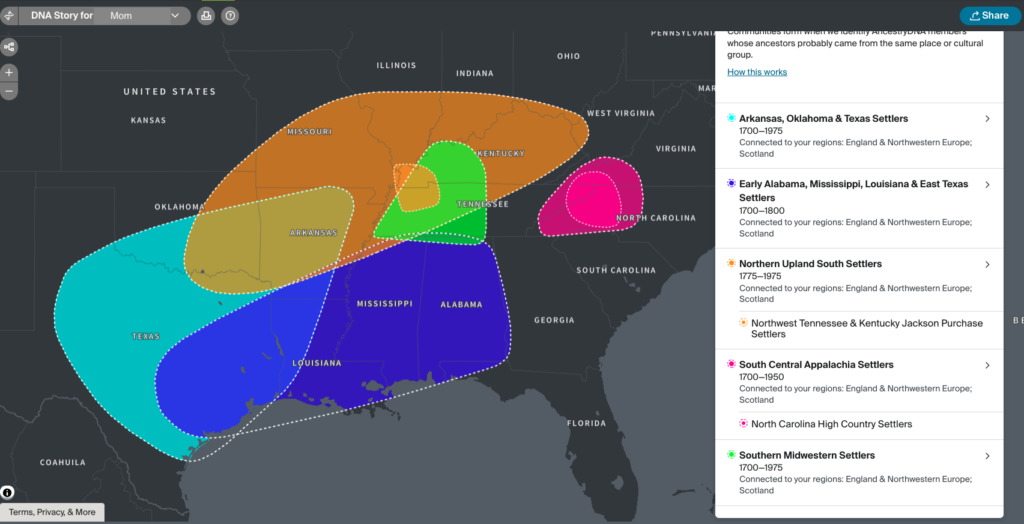

Here are my mother’s results:

Not only does my mother have the DNA community my brother had, Southern Midwestern Settlers (his is orange, hers is green), she has four others.

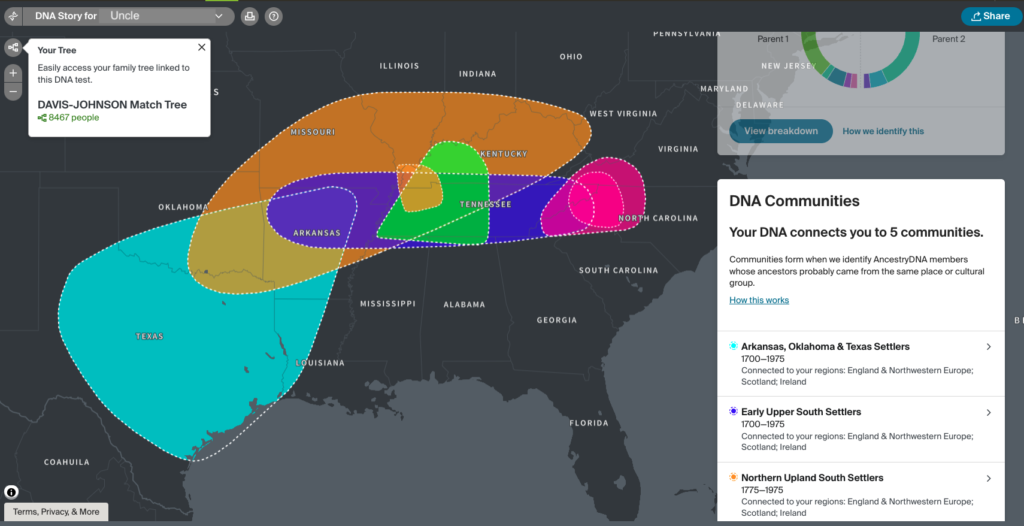

My uncle provided an additional community, Early Upper South Settlers:

The results differ a little, and that’s because of the different autosomal DNA they inherited from their parents (my maternal grandparents). The number of new communities demonstrates the rich genetic information older generations hold.

Here’s a comparison of the results for the four of us:

| Region | Mother | Uncle | Me | Brother |

| Arkansas, Oklahoma & Texas Settlers (1700-1975) | √ | √ | ||

| Early Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana & East Texas (1700-1800) | √ | |||

| Early Upper South Settlers (1700-1975) | √ | |||

| Lower Midwest & Virginia Settlers (1700-1950) | √ | |||

| North Upland South Settlers (1775-1975 Northwest Tennessee & Kentucky Jackson Purchase Settlers | √ | √ | ||

| South Central Appalachia Settlers (1700-1950) North Carolina High Country Settlers | √ | √ | ||

| Southern Midwestern Settlers (1700-1975) | √ | √ | √ |

The text describing the community, animated maps showing migration patterns, and hints from Ancestry provide clues that I can research. We don’t know anything about my maternal 2x great-grandmother, Mattie (Childres) Fisher Pike Adams outside of 3 marriages and 1 census. Ancestry placed this branch in the “Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas Settlers” with origins in Northwestern Europe and the British Isles, possibly migrating to the Chesapeake Bay area and moving across Tennessee and Kentucky. This is consistent with the Childres matches I am researching.

If I did not have my mother and my uncle, I would I would be missing five genetic communities. Perhaps in the next update, the DNA communities will show up for my brother and me. I welcome the new clues in my search for Mattie’s family.